Posted on: February 9, 2026, 07:21h.

Last updated on: February 9, 2026, 07:52h.

One of the most persistent beliefs about Karen Carpenter — the angel-voiced superstar who died 43 years ago last week — is that she collapsed on stage in Las Vegas, forcing the world to collectively confront anorexia for the first time. People even seem to know exactly which song she collapsed while performing: “Top of the World.” It’s a dramatic story — and a false one.

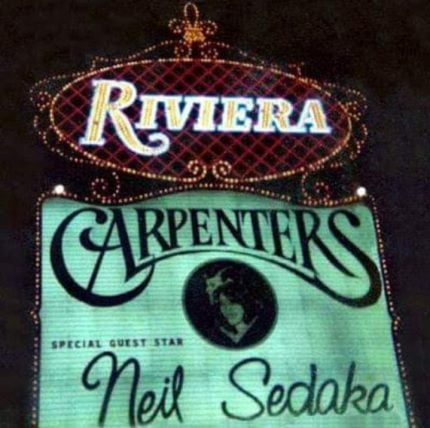

Carpenter did in fact collapse at the Riviera Hotel on Sept. 4, 1975. But it was backstage after a show, into the arms of Carpenters manager Sherwin Bash. She was treated by a hotel doctor and performed another two shows the following night.

Even scholarly sources mistake myth for reality. In “Skinny Blues: Karen Carpenter, Anorexia Nervosa and Popular Music,” a 2017 Cambridge University Press article, author George McKay wrote: “We might locate that colloquial inauguration of anorexia on a Las Vegas nightclub stage in the fall of 1975, when Karen Carpenter collapsed while singing ‘Top of the World.’”

They Only Just Begin

The Carpenters story begins in 1963, when Harold and Agnes Carpenter moved their children — Richard, 17, and Karen, 13 — from New Haven to Downey, Calif. Richard was a piano prodigy, Karen the kid sister banging out accompaniment on chairs with chopsticks.

Once Karen got a proper drum kit in 1965, Richard formed the jazz-leaning Richard Carpenter Trio with Wes Jacobs on bass and tuba. A year later, the group won a Hollywood Bowl battle of the bands. By her senior year, Karen was one of the best drummers the world had yet to hear of.

At Cal State Long Beach, the siblings headlined a harmony‑heavy act called Spectrum, a student‑formed group that foreshadowed their polished, radio‑ready sound. Their demo recordings reached Herb Alpert, co‑founder of A&M Records, who signed the Carpenters in 1969. Karen was only 19.

Their sophomore album, “Close to You,” exploded a year later. Its title single topped the charts; “We’ve Only Just Begun” reached No. 2. The duo went on to become a defining act of 1970s, selling more than 100 million records, winning three Grammys, and becoming fixtures on TV specials and variety shows.

But success created a problem. At 5’4”, Karen was invisible behind her drums. So the label pushed her to the front of the stage and hired another drummer. Being a frontwoman — not just heard but watched and scrutinized by the audience — made her feel naked and exposed. It triggered childhood memories of being teased by Agnes about her “pooch” when she weighed 145 lbs.

By the time stardom hit, Karen weighed a medically ideal 120 lbs., but she didn’t see herself that way. By 1975, her dieting had turned severe. She plummeted to 90 lbs.

In his Variety review of the duo’s September 1975 residency at the Riv’s Versailles Room, critic Bill Willard wrote: “Karen is looking painfully thin — almost to the point of being cadaverous.”

Willard didn’t stop there. He wrote that watching the show was like “watching a ghost perform” and that “you weren’t listening to the music so much as you were wondering how she was still standing.”

Myth Interpretation

The myth of Carpenter’s onstage collapse comes directly from The Karen Carpenter Story. Airing on CBS, it became the highest-rated TV movie of 1989.

In the 2010 biography Little Girl Blue: The Life of Karen Carpenter, Richard said that while he provided consultation, musical oversight and even Karen’s real clothes for actress Cynthia Gibb to wear for the production, he was forced by its producers to accept certain dramatic liberties.

“Karen didn’t collapse on stage,” he said, “but we’re dealing with a TV movie, so you have to take it with a grain of salt.”

The movie used the song “Top of the World” as the backdrop to emphasize the irony of her being at her lowest while singing her biggest hit, which was about how well life was going.

Another myth created by the TV movie that people still believe is that a 1973 review in Billboard magazine is what precipitated her eating disorder. It cruelly called Karen “Richard’s chubby sister.” (Following the movie, the trade magazine’s editorial team reported combing through every single issue from 1969 to 1980 for the comment and coming up empty.)

The Truth Was Ugly Enough

Though she bounced back from her backstage collapse at the Riviera, Karen’s condition worsened. On Sept. 14, four days after the Variety review became the perpetual 800-lb. gorilla in the showroom, Bash pulled them out of their residency with several dates remaining.

Two days later, Karen checked herself into Cedars-Sinai in L.A. But while medical science knew how to restore health to a malnourished body, it had nothing near today’s handle on treating the pathology of eating disorders.

Responding to the fallout from the Variety review and cancellations, A&M’s in-house publicists reached out to friendly journalists, pushing the narrative that Karen was battling a severe viral infection exacerbated by the Vegas heat.

But that couldn’t explain why more than 50 shows in Europe and Japan — including a Royal Command Performance before Queen Elizabeth II — were also suddenly canceled. So A&M hired Rogers & Cowan, the top music PR team of the era. Their official statement reframed Karen’s condition as “a severe case of physical and nervous exhaustion brought on by an unrelenting performance schedule.”

This wasn’t just spin — it was leverage. The Riviera had filed a $300K breach-of-contract suit against A&M for its canceled dates, which included a December engagement that hadn’t been announced yet. Positioning Karen’s condition as a medical emergency, instead of what back then was still considered a personal choice, helped the label negotiate a settlement. (Its details were never disclosed.)

The Riviera was also furious because, right before the crisis, Richard had fired opening act Neil Sedaka, whose older (and wealthier) fans the casino hotel had been relying on for gambling and dining revenue.

Richard was sore because Sedaka, a ’50s idol on the comeback trail, went over better than the Carpenters. He reacted to his thunderous applause by taking multiple encores, which made his set run long every night. (In Little Girl Blue, Sedaka remarked: “I didn’t know there was such a thing as being too good for the job.”)

Yesterday No More

The Carpenters returned to Las Vegas in July 1977. Still maintaining the increasingly unbelievable pretense that nothing was wrong, they played the MGM Grand (today’s Horseshoe). When they returned to their new venue a year later, in August and September 1978, it became the second Vegas residency they had to pull out of early. (This time, it was for Richard’s health. Suffering from a severe addiction to Quaaludes, he entered a six-week detox and took more than a year to fully recover.)

The Carpenters continued recording music and TV specials, but never toured again. (Their final concert was on Dec. 3, 1978 at the Pacific Terrace Theatre in Long Beach, Calif., a one-off benefit for the city’s symphony orchestra.)

In September 1982, Karen required another hospitalization. New York’s Lenox Hill Hospital placed her on IV nutrition.

During her two-month stay, she gained 30 pounds. But it was too late. The constant vomiting — and the ipecac syrup she secretly ingested to induce it — already damaged her heart beyond repair.

On Feb. 4, 1983, Agnes Carpenter found her daughter lying unresponsive on the floor of her childhood bedroom in Downey. EMTs detected a faint pulse, but Karen died of cardiac arrest in the ambulance.

She was only 32.

Look for “Vegas Myths Busted” every Monday on Casino.org. Visit VegasMythsBusted.com to read previously busted Vegas myths. Got a suggestion for a Vegas myth that needs busting? Email corey@casino.org.