[ad_1]

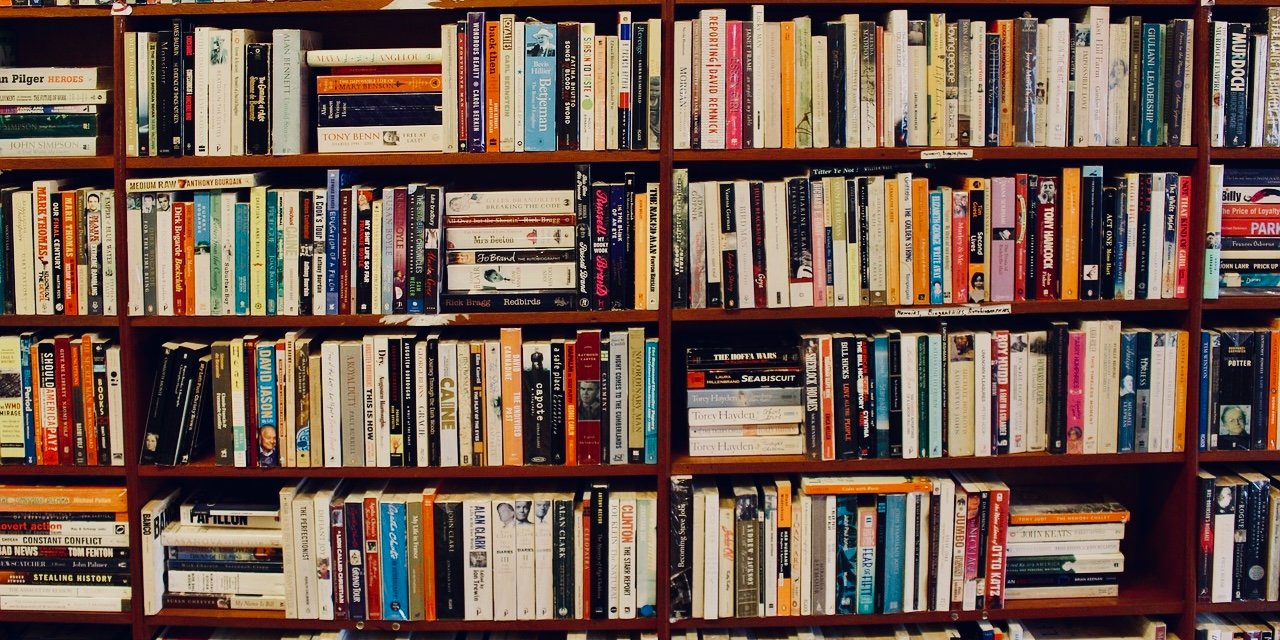

Mark your calendars! Our summer sale starts June 2nd!

Educators—this is your chance to stock up on volumes for your classroom! We’re offering three ways to save:

- 50% off select individual volumes

- $25 library sets

- Bulk pricing classroom sets

As always, shipping is free!

$6/copy and free shipping! Edited and excerpted to make the complexities of the content more accessible to the high school and post-secondary audience, each volume contains a background essay, thematic table of contents, topical appendices, and documents with a student-oriented introduction and discussion questions.

Interested in ordering more than 25 copies of an individual volume? Unit price is $4/copy and free shipping. Email us at [email protected] for more information.

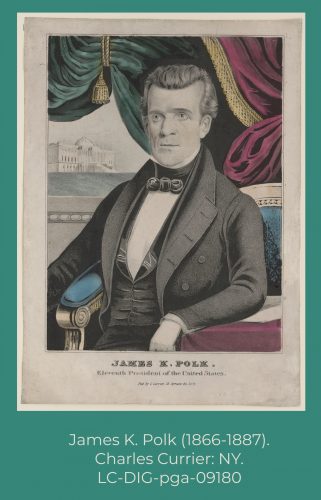

American Foreign Policy

American Foreign Policy covers the story of America’s foreign relations through the rise of the United States to great power status. Documents include:

- Alexander Hamilton, “Views on the French Revolution,” 1794

- President James Monroe, Monroe Doctrine, December 2, 1823

- President William McKinley, Message to Congress Requesting a Declaration of War with Spain, April 11, 1898

- Carl Schurz, “Against American Imperialism,” January 4, 1899

American Revolution

This treasury of firsthand accounts and other primary sources gives voice to the story of the American Revolution. Documents include:

- Deacon John Tudor, An Account of the Boston Massacre (1770)

- Prince Hall, et. al., Massachusetts Antislavery Petition (1777)

- Private Hugh McDonald, The Continentals Encounter Civilians (1777)

- Eliza Wilkinson Encounters Redcoats in South Carolina (1779)

- “Plain Truth,” “To the Traitor General Arnold” (1781)

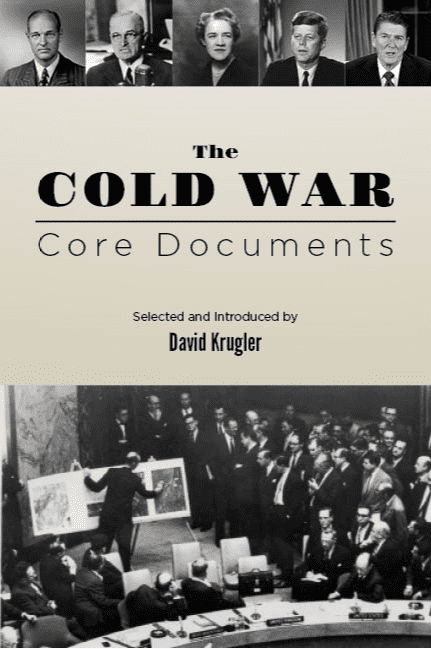

Cold War

The Cold War covers American aid to Europe in the early years of the Cold War and American intervention in subsequent years in conflicts around the world to contain the spread of Soviet power. Documents include:

- Irving Kaufman, Sentencing of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, 1951

- U.S. State Department, The Negro in American Life, 1952

- Rusk and McNamara, Report to President Kennedy on South Vietnam, 1961

- Students for a Democratic Society, The Port Huron Statement, 1962

- National Security Council, National Security Directive 23, 1989

Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787

Madison wanted to leave his notes on the Constitutional Convention to posterity, and left the final decision of what should appear in print to his wife, Dolley Madison. The several editions published since his death, however, have moved further away from what the Madisons wanted published. This volume is a faithful attempt to recreate Madison’s vision for his “Report on the Debate.”

Great Depression/New Deal

This collection of documents on the Depression and New Deal makes clear the reasons why and the degree to which Franklin Roosevelt intended the New Deal to be a re-founding of the American republic. The collection also presents the arguments of those who opposed the New Deal — Democrats as well as Republicans — and those who thought it did not go far enough. Documents include:

- Representative Jacob Milligan, Speech on the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930)

- E.E. Lewis, “Black Cotton Farmers and the AAA” (1935)

- Senator Huey P. Long, Statement on the Share Our Wealth Society (1935)

- Al Smith, “Betrayal of the Democratic Party” (1936)

- Roosevelt, “Fireside Chat” on “Purging” the Democratic Party (1938)

Populists and Progressives

Populists and Progressives highlights thinkers who translated the late 19th century American experience with industrialization and urbanization into political ideas and reforms that influenced 20th century American politics. Documents include:

- Henry George, Progress and Poverty, 1879

- William A. Peffer, “The Mission of the Populist Party,” December 1893

- W. E. B. Du Bois, The Niagara Movement’s “Address to the Country,” 1906

- Theodore Roosevelt, “The Right of the People to Rule,” 1912

- John Dewey, “The Crisis in Liberalism,” 1935

Religion in American History and Politics

This volume draws together twenty-five primary documents through which readers may trace central themes in the long, complex story of religion and politics in American history. Documents include:

- Laws, Rights, and Liberties Related to Religion in Early America (1610-1682)

- Washington, Letter to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island (1790)

- Abraham Lincoln, The Temperance Address (1842)

- Martin Luther King, “Can a Christian Be a Communist?” (1962)

- Barack Obama, Address at Cairo University (2009)

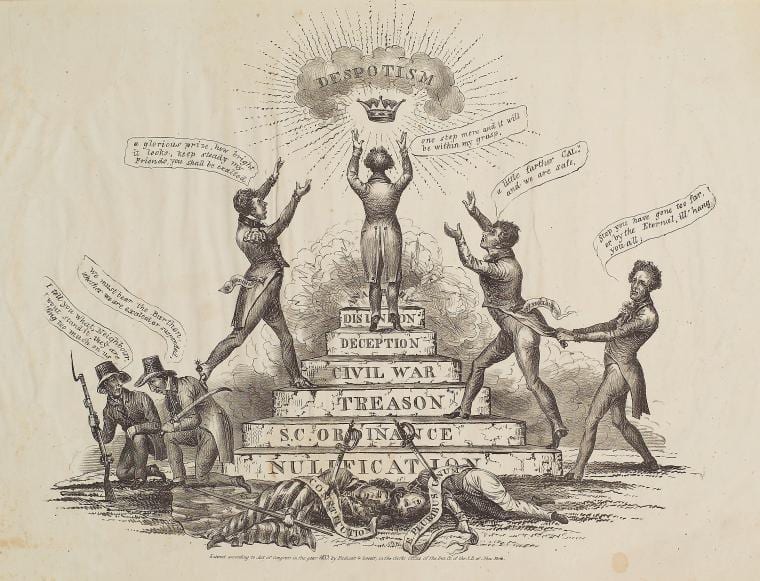

Slavery & Its Consequences

Slavery & Its Consequences addresses the codification of race-based chattel slavery and the related grievous problem of racial prejudice, as well as the development of a principled resistance to both slavery and its social, cultural, and political effects over the course of four centuries. Documents include:

- John Laurens, Envisioning an African American Regiment, February 2, 1778

- Alexander Crummell, The Race Problem in America, 1889

- W. E. B. Du Bois, “Returning Soldiers,” May 1919

- Daniel Patrick Moynihan, The Negro Family, March, 1965

- Ta-Nehisi Coates and Stephan Thernstrom, Reparations for Slavery, 2007, 2019

The Supreme Court

This collection highlights the landmark cases in American jurisprudence. Documents include:

- Dred Scott v. Sandford, 1857

- Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896

- Gideon v. Wainwright, 1963

- Roe v. Wade, 1973

- District of Columbia v. Heller, 2008

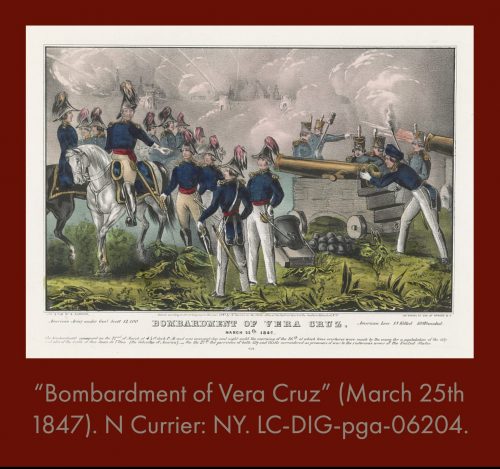

Westward Expansion

The documents in this collection present the reasons Americans gave for and against westward expansion and their thoughts on the political, moral, and economic issues it raised. Documents include:

- Narcissa Whitman, Letters and Journals from the Oregon Trail, 1836

- John O’Sullivan, “Annexation,” July 1845

- The Farmers’ Movement, 1873–1874

- The Ghost Dance Religion among the Sioux, 1889–90

- Senator Albert J. Beveridge, “The March of the Flag,” 1898

History Library

- American Revolution

- Slavery & Its Consequences

- Westward Expansion

- Great Depression and the New Deal

- Cold War

Government Library

- Religion in American History and Politics

- The Supreme Court

- Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787

- American Foreign Policy

- Populists and Progressives

Mark your calendars! Sale runs from June 2nd–July 18th or until supplies last!

[ad_2]

Source link