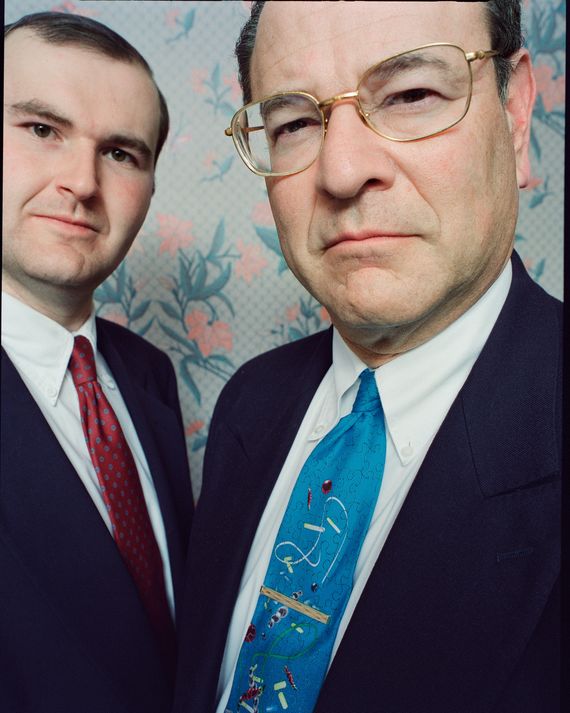

Mark (right) and David Geier, in a 2004 photograph for Seed magazine.

Photo: Jason Gould

In 1970, a 22-year-old named Mark Geier showed up at the tennis court on Democracy Boulevard in Bethesda, Maryland, not far from the National Institutes of Health. He wore round plastic glasses and thick muttonchops, and he had a disdain for authority and a belief in his own cunning. Five years earlier, he had been ranked the 15th-best Ping-Pong player in the country. Geier played tennis like he played Ping-Pong, and he played Ping-Pong like he played chess. He didn’t win on strength; he won on intelligence and intuition. He often stood at the net and put the ball where he knew his opponent couldn’t reach it. Geier’s girlfriend was the daughter of a tennis pro who taught many powerful men how to play: the Kennedys at the Breakers hotel in Palm Beach, Florida; Defense Secretary James Forrestal at the Chevy Chase Club in Maryland; Vice-President Henry A. Wallace; astronaut Michael Collins. Geier had recently graduated from George Washington University with bad grades. He liked winning. He wasn’t particularly athletic.

One day, Carl Merril, an iconoclastic researcher who worked at the leading edge of philosophy and biology, came to the court as well. Merril was a man who, as a child during summers on Long Island, had delighted in learning advanced math. He mystified a lot of his NIH colleagues by studying bacteriophages — viruses that infect bacteria — and suggesting that they could be used to treat infectious disease. He considered himself “a real nerd, not into sports.” But he wanted to learn tennis. Geier proposed a deal: He would teach Merril tennis if Merril gave him a job. Merril didn’t have any suitable positions open in his lab. Geier settled for a gig as a volunteer.

At that point, science was ascendant — a miracle, a religion. The first ARPANET message had just been sent, the first artificial heart implanted. Neil Armstrong had landed on the moon. Geier was a quick learner — and a bit lazy. He easily mastered all the lab techniques Merril considered necessary, but his inquisitiveness and effort stopped there. With a shock of dark hair and a habit of telling people if he thought they were stupid, Geier polarized the lab. Some loved his gumption; others hated his cockiness, a dynamic exacerbated by his remarkable good luck. As Merril recalled, he let Geier “move some petri dishes around” in an experiment that turned into a landmark paper, published in Nature, about introducing bacterial genes into human cells. Geier was one of three co-authors. President Nixon called to congratulate the team. The day the TV crews arrived, Geier showed up to the lab in what Merril described as a “Liberace jacket” — neon colors, sequins: “He danced around, he rolled around, and grabbed each flask and put it, with a flourish, into the incubator.” Geier was livid when the clips that aired showed only his wrist.

Geier wanted to go to graduate school, but his poor grades kept him from getting in. Then a director of a lab with ties to Columbia saw him play tennis. “Anybody who plays tennis like that, I’ll get them into Columbia,” he told Merril. But once there, Geier had a hard time. He failed to treat his professors with the respect to which they were accustomed. Merril recalled one describing him as “uneducable.” He returned to D.C. and finished his Ph.D. in genetics at George Washington University. For his thesis, Merril said, “he basically took the work I published in that Nature paper that got all the publicity and embellished some.”

After the Ph.D., Geier continued working in Merril’s lab. In 1973, the lab discovered bacteriophage in the fetal-bovine serum used to make some vaccines. At that point, a handful of vaccines were made with whole cells, not just isolated proteins from pathogens. The live cells needed to be cultured in a medium — hence the fetal-bovine serum. Gina Kolata, then a cub reporter, now a 38-year veteran of the New York Times, wrote an article about the finding in the journal Science. In it, she paraphrased Merril as saying he feared the government was not acting quickly enough to get the bacteriophage out of the vaccine supply, given how little we knew about it.

Fears about vaccines have existed for as long as there have been vaccines (smallpox, 1796). Who wants to get an injection when you are healthy and the side effects could make you feel even temporarily a little sick? Toss in the vagaries of living in a human body, a contraption so sensitive and varied that pretty much anything, under the right circumstances, will kill someone. Add the human brain’s poor aptitude for balancing emotion and statistical risk. Achieving and maintaining herd immunity was always going to require disciplined public-health messaging. Especially after all 50 states passed school vaccination requirements and almost nobody had firsthand experience anymore of the diseases vaccines protected against. Merril wrote a letter to the editor of Science saying Kolata had misrepresented him: “I have never advocated that ‘no more phage-contaminated vaccines should be sold.’ The currently employed live vaccines have had a clearly demonstrated beneficial effect against acute human diseases. To withdraw such vaccines from the public with no immediate substitute would represent a threat to the nation’s health.”

Nonetheless, a few months later, a lawyer called Merril’s lab to see if he would testify as an expert in a case against a vaccine manufacturer. Merril declined — he saw where this was going and wanted no part of it. Geier overheard the call and asked, “Can I do that?”

Merril said, “I have no control over what you do.”

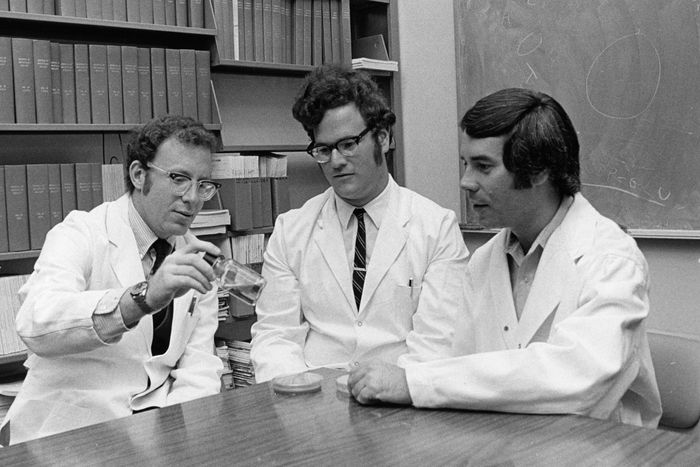

1971: At the NIH, Mark Geier (center) would learn about the opportunity to testify as an expert witness in cases against vaccine manufacturers.

Photo: Courtesy of Carl Merril

This could have been a throwaway exchange — another man might have gone home and forgotten the dollar signs that flashed before his eyes at the prospect of vaccine torts. Or he could have remembered the torts but not encountered a world of parents who felt the rush of growing political capital as they, not the doctors, became the ranking experts on their children’s health. Geier, however, ran headlong into all this and as a result unleashed a force that would reshape American politics.

For a while, Geier didn’t do much that changed the course of history. He completed a medical degree at GW and trained as an OB/GYN. He married the tennis pro’s daughter, and the two became a formidable mixed-doubles team. In 1980, they had a son, David, and Geier left Merril’s lab. He opened several side businesses with fellow M.D.’s. One, Genetic Consultants, offered amniocentesis and genetic counseling.

Yet Geier took to the role of expert witness with unusual enthusiasm. His primary goal, a friend from the time explained, was “to make a name for himself.” Between 1985 and 1989, Geier consulted or testified in nearly 50 vaccine cases. Many involved families who believed a child’s encephalopathy, or brain damage, resulted from the whole-cell diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP) vaccine. (No causal relationship has ever been established between the two; many neurodevelopmental disorders arise in early childhood and thus can appear to have been triggered by vaccines.) This was the same period during which the U.S. government set up a dedicated vaccine-injury adjudication program. The country had become increasingly litigious — and spooked by immunizations after a TV special called DPT: Vaccine Roulette told parents the real question about DTP isn’t whether it causes damage. The real question is how often. (One could raise a similar question about peanut butter: The real question isn’t whether it kills people but how often.) The so-called vaccine court served two functions. It enabled families of children with acute adverse reactions to be compensated without too much hassle. It also limited liability for vaccine manufacturers and thus kept them from abandoning the U.S. market.

Geier was a great talker, “a person who could sell refrigerators and freezers to the Eskimos,” according to a co-worker in Merril’s lab. He was also a person who felt the rules “weren’t meant for him.” Geier kept consulting and testifying and made a lot of money. Through the late ’80s, vaccine-court officials found his testimony “credible and convincing.” But by 1990, they were onto him for his loose and convenient relationship to facts, his propensity to testify with medical certainty that vaccines were to blame for whatever misfortune a family brought to vaccine court. In 1991, the court admonished “Dr. Geier to reconsider his role, from an ethical and moral standpoint, as a witness.”

Once manufacturers stopped making whole-cell DTP vaccines, the next major catalyst for vaccine fears was a preservative called thimerosal. Thimerosal contains ethylmercury, and in ramping up the country’s pediatric immunization program to include hepatitis B and Hib, the Food and Drug Administration did not pause to study the effects of the combined thimerosal load. Meanwhile, mercury causing harm was in the news; studies suggested that women who consumed a lot of seafood during pregnancy put their children at risk. A rising-star environmental lawyer named Robert F. Kennedy Jr. championed this issue.

In 1997, Congress mandated the FDA to review mercury levels in all food and drugs. This revealed that the combined ethylmercury load in all the infant vaccines was 187.5 µg. This number — 187.5 µg — was higher than the FDA’s limit for how much methylmercury a baby should consume orally.

Ethylmercury, methylmercury — all anyone heard was mercury. Yet the two are different molecules. As Seth Mnookin writes in The Panic Virus: A True Story of Medicine, Science, and Fear, “A good parallel of the difference between ethylmercury and methylmercury is that of ethyl alcohol, or ethanol, and methyl alcohol, or methanol: Two shots of the former give you a buzz; two shots of the latter are lethal.” This distinction was lost on worried parents, especially after a telegenic British doctor named Andrew Wakefield published a Lancet paper in 1998 linking the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine to autism in eight children.

The following year, the FDA recommended removing thimerosal from immunizations. It had no evidence of its harmfulness, but neither did it yet have sufficient data to prove it was safe. The decision was rushed — made over a three-week window in the summer of 1999 — and the announcement left many parents anxious and confused: “The current levels of thimerosal will not hurt children, but reducing those levels will make safe vaccines even safer.” What? This left a wide-open shot for an expert tactician with a desire to prove a child had been injured by a vaccine.

In 1997, Lyn Redwood, a nurse in Atlanta with a 4-year-old autistic son, started researching autism online. She had lost faith in conventional doctors after one told her, “There’s nothing I can do for your son Will. Why don’t you just take him fishing?” On the new World Wide Web, she found a group of similarly aggravated parents. Sure, we’d put men on the moon. But where was the autism cure? This question led her to an autism conference. There, she heard Wakefield speak. He was handsome and had a posh British accent. Redwood felt “awestruck,” she told a reporter, by how much her son’s symptoms sounded like mercury poisoning. She launched a listserv for parents to share thoughts about the autism-mercury connection. The listserv quickly became, Redwood said, “a community and a movement.”

The crowd was not low-key. Redwood soon linked up with Sallie Bernard, a marketing consultant with an autistic son and an investment-banker husband; the couple met as freshmen at Harvard. Also Mark Blaxill, a Harvard M.B.A. and a partner at Boston Consulting Group with an autistic daughter. “If what Wakefield is saying is true, then we have a very dramatic and simple story,” Blaxill posted online after attending an autism conference. “An incredible tragedy” of epic proportions, “created by a massively misguided public health initiative.”

The group took the name SafeMinds and recruited the daughter of Indiana Republican representative Dan Burton.

This cohort of parents didn’t just feel concerned. They felt aggrieved, and they approached the task of advocating for their children not as supplicants begging for care from a paternalistic welfare state but as bosses demanding more from inept employees. This all made sense. In the late 1960s, the U.S. began deinstitutionalizing children with cognitive disabilities. Your child was yours to care for in your house. Parents, not doctors and researchers, were now the experts. Direct observation of children at home was valued more than double-blind studies. This mind-set enabled parents to “eliminate the middle man,” as Gil Eyal writes in his book The Autism Matrix. You could jump from direct experience to proof.

Bernard, the marketing consultant, took control of SafeMinds’ communications. To gain credibility with a wide audience and thus consolidate political power, she argued, they needed to publish a paper in a medical journal. In 2001, “Autism: A Novel Form of Mercury Poisoning,” its lead author one “S. Bernard,” ran in Medical Hypotheses, a publication that is open to “radical hypotheses which would be rejected by most conventional journals.” The paper took commonplace symptoms observed in autistic children (and children in general) — diarrhea, vomiting, and temper tantrums among them — and suggested these symptoms revealed that autism was caused by mercury poisoning.

SafeMinds and Geier were not yet allies. Geier was living in Silver Spring, Maryland, in a house with a Ping-Pong table in the basement, a clay tennis court in the backyard, a room filled with sports trophies, a refrigerator stocked with meat and Diet Coke, and an office and lab suite where he sometimes saw patients. The gestalt of the home was chaos: piles of newspapers and tennis-racquet covers on the dining tables, the neckties Geier threw on for client appointments shoved in drawers. Promptness, for him, was not a priority. Some days he woke up at 10 a.m. for a 10 a.m. patient, then showered, dressed, and ate breakfast. Reviewing and signing lab results was not a priority either. Geier purchased a rubber stamp of his signature and gave it to his head lab tech. She refused to use it and often drove to the Geiers’ house and thrust the papers in front of Mark while he was on the tennis court.

David, the Geiers’ only child, looked like Mark: same round face, same small dark eyes. He played tennis like Mark, too. “He was a replica of Mark,” David’s high-school tennis coach told me. “They were just extremely, extremely close.” Mark and David entered father-son tennis tournaments and showed up not just with matching aggressive, analytical styles of play but in similar collared blue-and-white shirts. Merril described the two as “attached at the spinal cord.” Anne, Mark’s wife, was the best tennis player in the family. Over the years, the Baltimore Evening Sun described her as “a human backboard” and a “nursery school teacher who always wins but seldom speaks.” She was not concerned with social graces, either. Once, Merril asked her what would be the best thing he could do for his tennis game. Anne said, “Quit.”

Some of David’s schooling took place around his father’s Ping-Pong table, where mathematicians like George Hutchinson came to play — and taught David a little statistics on the side. In his teen years, David started using those skills to keep detailed statistics about Mark’s tennis matches. “It evolved into this thing where David is wearing a white medical coat and a stethoscope and Mark is molding him into his assistant,” another friend from those years said.

As Merril put it, “He basically would do anything to please his father. To David, his father was a god.”

In 1998 — the year after Redwood first started thinking about autism and mercury — David was a freshman commuter student at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He became president of MedCon, a medical-legal consulting shop. David’s duties, according to his CV, included running “epidemiologic analysis” of large databases of vaccine injuries. Using this, father and son started co-publishing dozens of papers on the hazards of vaccines. These were useful to petitioners in vaccine court. In 2001, when Bernard published her study, autism had not yet entered the Geiers’ portfolio. Mark saw parents like Redwood and Bernard as a nuisance at best. “We kept saying, ‘Look, you’re not helping,’” Mark later said in a deposition, the we referring to David and himself. “We’re trying to fix the vaccines. We love vaccines. We want to make the program better. You keep running around saying these things, this tiny bit of thimerosal … is causing a problem.”

As Mark told the story, parents of autistic children hounded him and David to help get their message out. “My son actually was fairly aggressive with them,” Mark said in his testimony, “and told them, if you keep bothering me, we’re going to testify that it doesn’t cause and you’re really hurting the issue.”

Mark took this as a parenting moment. “I told him, these women, they’re wrong, but after all, they do have affected children. You have to be polite. You have to be nice.”

“If we help you a little bit, will you go away?” Mark said he asked one of the mothers. So, according to Mark, he told her how to design a study of thimerosal and autism. You amass a very large sample population — say, a million children. Then you define a control group: in this case, children who will receive no vaccines. Then you compare the autism rate in children who receive thimerosal-containing vaccines with children who receive no vaccines. But, as he recalled in his testimony, he told her she couldn’t do the study: “It’s unethical to not vaccinate children. So you can’t do the experiment. Now go away, don’t bother us anymore.”

2002: At a House Government Reform Committee hearing on autism and childhood vaccines.

Photo: C-Span

2009: Mark (left) and his son, David (not pictured), developed a treatment protocol for autistic children using Lupron.

Photo: Photograph by Chicago Tribune/TCA

Still, Geier had a genius for opportunity. Within a year, father and son were on the autism circuit — talking to parents at conferences, researching the dangers of thimerosal, and testifying at congressional hearings such as “Vaccines and the Autism Epidemic,” moderated by Representative Burton. Their father-son dynamic remained codependent and strange. “Mark needed David to make sure that his fly wasn’t undone, and David needed Mark to have a purpose,” said Mnookin, who spent years reporting his book. If Wakefield was the movement’s charismatic visionary, the Geiers were its on-the-ground functionaries, the men who took his ideas and spread them across the country’s courtrooms, legislatures, and doctors’ offices. This made them heroes to parents. “It wasn’t quite like the Beatles showing up,” Mnookin said. “But apart from Andrew Wakefield and Jenny McCarthy, there was no one who was treated with more reverence and idolization.”

The Geiers’ studies sometimes relied on methodology questioned by experts — say, choosing cases and control groups from different time periods with wildly different vaccination rates. (With techniques like this, explains Jeffrey S. Morris, a professor of biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania, you can link just about anything: live births and cell-phone usage in Sri Lanka, pancreatic cancer and time spent on Facebook.) Yet the details of the Geiers’ statistical analysis hardly mattered.

The belief that mercury had poisoned children led to an inevitable question: How to get the mercury out of them? Some parents of autistic children turned to chelation — a 1930s therapy for heavy-metal poisoning. Geier saw an opening: What if he and David launched a chain of autism-treatment clinics? Mark was not trained as a pediatrician, or as an endocrinologist, or as a neurologist. David had taken graduate-school classes but did not earn an advanced degree. Still, they devised a treatment protocol: In addition to offering chelation, they would prescribe to children who met test criteria shots of Lupron, a drug that lowers testosterone. They had heard again and again from parents about meltdowns so bad that their children turned violent; about children, oblivious to social cues, masturbating in public. Dressed in identical blue blazers, white shirts, and red ties, the Geiers presented their new therapy to parents at conventions like AutismOne. “Testosterone makes aggressive behavior, mercury poisoning makes aggressive behavior, regressive autism makes regressive behavior — the story becomes fairly clear,” Mark would explain.

Lupron’s common uses were for treating precocious puberty and prostate cancer and for “chemically castrating” sex offenders. Mark allowed that he was “not happy with trying it out on children without further research.” But he’d deduced, as he put it in a deposition, that “these people are desperate.”

“Autism instructed my soul in desperation,” Lisa K. Sykes, a Methodist minister, wrote in her memoir, Sacred Spark. She worried that witnessing her son Wesley’s “sporadic and indescribable agony” would make her not the “sum of my strengths” but “less than the total of my weaknesses.” She tried chelation with Wesley; maybe her “toxic” son could be cured. At a 2004 meeting where the Geiers were speaking, she brought an eight-foot banner of Wesley’s chelation data, what she described as his “graphed mercury dumps.” She later approached the Geiers: “Forgive me for asking this, but if Wesley fits this profile you’re speaking of with the high testosterone, would you treat my son?” Wesley became their first patient.

To Sykes, the Geiers proved to be saviors. She’d been troubled by Wesley’s erections in the shower, his biting, his tantrums. One big intramuscular shot of Lupron a month and a smaller subcutaneous shot daily and, Sykes wrote, Wesley “was being recreated and resembled more and more the child I knew God had intended him to be.”

The Geiers started including Wesley as a case study in their Lupron talks in 2005. “Many of these autistic children — they’re just not acceptable members of their family. They’re isolated. They’re doing strange behaviors,” David said to his audience. “All this seems to be ameliorated by the Lupron.” The Lupron worked through what he described, in impressively science-y language, as “the testosterone-and-mercury complex classically in the body.” The testosterone forms “long strands like little threads,” and mercury “comes in and binds one string of testosterone to another one,” creating, “in effect, a testosterone mercury sheet … It’s going to be very tough to get rid of both of them.

“If you can fix it,” which David promised you could through chelation and Lupron, “the autism severity — and maybe autism altogether — may disappear.”

Meanwhile, the autism community was splintering. Kathleen Seidel, a mother of an autistic child, anchored the opposing side on a blog called neurodiversity.com, where she would chronicle the Geiers’ exploits in a 16-part series, each post meticulously sourced with hyperlinks. Here, in Seidel’s world, citizens remained faithful to the scientific method. Institutions were flawed but basically good. Autism wasn’t a toxicity to be cured. It was a difference, perhaps even an identity. Maybe Andy Warhol was autistic! And Nikola Tesla! Ludwig Wittgenstein! Wakefield’s study was partially retracted in 2004 (and fully retracted in 2010) due to fraudulent data and undisclosed conflicts of interest. Good riddance.

Seidel’s side and the Geiers’ side had no shared logic, no shared apprehension of facts. For Seidel’s camp, the many replicated large studies that showed no link between vaccines and autism proved (as virtually all scientists agreed) there was no link between vaccines and autism. For the Geiers’ camp, it proved the existence of a vast conspiracy. As Kennedy wrote in “Deadly Immunity,” an article that ran in Rolling Stone and on Salon in 2005 — and was later retracted — “public-health authorities knowingly allowed the pharmaceutical industry to poison an entire generation of American children.”

Around that time, a mother heard the Geiers give a presentation at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. She had four children from her first marriage, each with autism more severe than their next-elder sibling. For years, she’d been driving all of them around in their minivan, visiting conventional doctor after conventional doctor, trying new medications, altering doses. She’d put her family on a diet heavy in fermented foods; she’d replaced all of their bedding and their cleaning products. Yet her youngest son’s behaviors remained severe. He would bolt out the front door and run into the street. During his meltdowns, he had “unreal strength,” the eldest of the four children told me recently. He scared everybody. “Especially after he hit puberty,” she said. “He became extremely violent, extremely loud and screamy.” At times, she said, “my mother had to send him away to group-home settings.”

“We are very excited about what the Geiers are doing and have already done so far in our family!” the mother posted in early 2007 on a Yahoo autism message board, nearly the entirety of which Seidel saved in a Word document. “I feel like for the first time in over 10 years like we may have a promising future!”

The Geiers opened a chain of ASD Centers to see patients in person in Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Missouri, New Jersey, and Texas. The first step for a typical family who sought their Lupron protocol was some $1,200 in tests. The deep intramuscular shots hurt. Still, some parents were thrilled and came back to the message boards to report: “TREMENDOUS GAINS IN BEHAVIOR”; “she seems like a fog has been lifted”; “increased attention span, the loss of her tactile defensiveness (I’m allowed to hug her now).” Others were nonplussed: “peeing all over the house”; “a slight improvement at first but now only regression.” One father wrote, “My daughter is becoming more and more afraid” of the office where she receives the Lupron shots. “She KNOWS the outside of the building, the waiting room … The closer we get to the final room, the more she resists.”

Members of the neurodiversity community traveled over to the Lupron listservs and started making comments like, “From reading about Lupron, i wouldnt touch it with a barge pole. I guess I don’t need a ‘fixit’ certificate that badly for my child.” On the other side, people took to calling Seidel “that Kathleen” and her cohort “ignoramuses” who “only pay attention to flawed epidemiology” and “who would rather keep autistic children exactly the way they are.”

“I just can hardly tolerate IGNORANT people who speak about something they have NO KNOWLEDGE about! It is people LIKE YOU that ridiculed me when I was considering not immunizing in the first place … You are obviously not living with autism, and what *yes* vaccines ****without a doubt**** have done to our kids!” one mother wrote. “Thank GOD for the Geiers … The road we were headed before the Geiers was a dead end … endless medication from a medical community of doctors that want to mask the symptoms instead of treat the problem … GET YOUR FACTS STRAIGHT!!!”

2016: Appearing before the Maryland Court of Special Appeals in a case stemming from claims that David Geier practiced medicine without a license.

Photo: Courtesy of Maryland Judiciary

2025: Kennedy defends David Geier at a Senate hearing.

Photo: John McDonnell/AP Photo

This shouty, split-screen world is the world we all live in now: a disorienting, bifurcated bad trip of a universe in which one person’s hero is another’s villain. “Make America Healthy Again” is as obvious and necessary as sunshine or as evil as poison. All the institutions are crumbling. Everyone here feels insane. How did we even come to need a phrase like consensus truth?

For a while, it seemed as though science and the Establishment had regained the upper hand with the Geiers. In late 2006, the Maryland Board of Physicians began investigating a complaint alleging Mark was “experimenting on children without a rational scientific theory.” A later complaint alleged that David practiced medicine without a license. Mark lost his medical license; David was fined. Later, the Florida Board of Health investigated Mark for compounding Lupron (they later settled, with Mark effectively pleading no contest and paying a fine). But rather than cowing the Geiers, the censure energized them. In 2007, Mark stood behind a podium in front of the CDC building and roused a mercury-free-vaccine rally by denigrating the people inside. “These people, they’re not M.D.’s,” he said. They just knew “how to do risk communication, which is another way of saying ‘how to lie.’” The Geiers also countersued the Maryland Board of Physicians for $6 million, claiming that, in its proceedings against the Geiers, the board had shared their private information. Still, the board’s original ruling held.

Childhood vaccines had been thimerosal free since 2001. Through the 2010s, autism cases continued to rise. Father and son branched out to other diagnoses. They started writing papers about the relationship between human-papillomavirus vaccines and autoimmune disease and whether lead exposure is linked with ADHD. They began presenting at dental conferences, trumpeting the hazards of mercury in amalgam fillings.

The last time the Geier men appeared on TV together was on an Ohio Fox affiliate in October 2022. Mark was then 74 and David 42. Mark, identified on the chyron as Dr. Geier, explained that most Americans had been duped by mainstream dentists. “If you have a silver filling, it’s not actually silver; it’s mercury,” he said. And mercury is a “highly toxic substance” currently in the mouths of “58 percent, or 91 million,” of American adults.

David then spelled out the URL of a website of dentists who were fighting to remove fluoride from public water supplies.

The families the Geiers treated still loved them. “The Geiers saved us. They saved us so much grief,” another mother, in Idaho, said. Pre-Lupron, her autistic son slept only two hours a day. He was violent with himself and others. Lupron calmed his meltdowns and curbed his sexual impulses. The Geiers made the families feel like they came first.

Mark died on March 20, 2025. One week later, Kennedy installed David to “advise other scientists on how to find the ‘lost’ data and reaggregate” a dataset of vaccine injuries, as Kennedy posted on X. (David did not respond to repeated requests for comment.) Kennedy also reportedly hired Lyn Redwood to help oversee vaccine safety in general.

Insiders suspect David’s real job is to try to repeat a 2003 study that showed, in its preliminary data, a tiny link, outside the margin of statistical relevance, between infant vaccines and a wide range of neurodevelopmental disorders. Redwood embraced this as proof that vaccines cause autism. “My god,” she reportedly said to herself. “Our worst fears were true.” Upon deeper analysis, however, the chimera of a connection faded. If David does indeed release a study implicating vaccines in autism, “it’ll be cataclysmic,” Del Bigtree, a director of a group called MAHA Action, said at an autism conference this past spring. “For some, there will be gnashing of teeth; there’ll be great fear and terror … but there will finally be truth.” Meanwhile, vaccine stalwarts like Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, see a great fear and terror, too. One scenario Offit laid out is that Geier’s study propels Kennedy to alter the rules of vaccine court: “Either he adds autism to the list of compensable injuries, which would be devastating to that program — you would quickly exhaust the money that’s currently in the system.” Or he disbands the vaccine court and lets manufacturers “suffer the slings and arrows of civil litigation.” And this drives vaccine-makers out of the U.S. market, leading to shortages and a country even more vulnerable to outbreaks.

The same characters who forged autism’s anti-vaxx movement are now managing our country’s public-health system, building out the sociopolitical cosmos they broke ground on decades ago. Here, the language of science is more potent than the findings of science. Here, even inside the Department of Health and Human Services, the ethos of parenting — of fighting for a particular child, of giving primacy to emotional need — has supplanted the ethos of public health, of making decisions to best serve the health of all. In 2020, when COVID hit, this alliance already had a fleshed-out ideology of vaccines as part of a government-pharma conspiracy. The pandemic expanded the potential constituency for those ideas to the whole country.

What comes next? Who knows. The erosion has already begun. Trump’s One Big Beautiful Act, passed in early July, cut a trillion dollars from Medicaid. Utah and Florida have banned fluoride from drinking water; legislatures in Louisiana, South Carolina, Nebraska, Kentucky, and Massachusetts are considering doing the same. Are antibiotics at risk? Kennedy’s MAHA report, released in May, suggested antibiotics cause increases in childhood asthma, obesity, and ADHD.

In 2001, two years before the Geiers started publishing on autism, 94 percent of American parents considered it “very” or “extremely important” for their children to get vaccinated; in 2024, that number dropped to 69 percent. In the 20th century, before vaccines, there were on average 530,217 cases of measles annually in the U.S. More than 1,250 measles cases have been reported in 2025 so far, the highest number of any year since 2000.

This summer, on the tennis courts on Democracy Boulevard, kids attend summer camp and NIH employees grieve. Fifty years ago, Geier outplayed everybody here, not on strength, skill, or speed. He outplayed them by spotting opportunity and weakness. In politics, including public health, rhetoric and emotion defeat reason. Geier understood this. He beat the men of science by putting the ball where they couldn’t reach it.