(RNS) — The film director and music producer Jeymes Samuel, best known for his work as a music consultant on Baz Luhrmann’s “The Great Gatsby,” reminisced to an illustrious gathering of Black Hollywood luminaries about watching “Jesus Christ Superstar” as a boy.

“And I was like, this is cool but where are the Black people? Like the only Black person in the whole thing was Judas!” This got a laugh from the crowd at the David Geffen Theater at the Academy of Motion Pictures, which included Angela Bassett, soul music icon Seal and comedian Dave Chappelle, but Samuel pushed on. “It’s fair for us to at least have one of these films that we can see ourselves in,” he said.

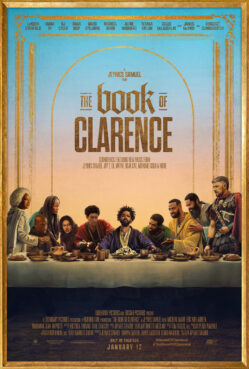

Samuel was there to introduce just such a film: “The Book of Clarence,” an irreverent biblical comedy, produced by the rap star Jay-Z, that counters decades of whitewashed and stiff-necked biblical narratives. The movie, written and directed by Samuel, hints at how much more compellingly Jesus’ story could be told if it were told like Clarence’s.

Clarence, played by LaKeith Stanfield, is a first-century hustler out to prove that he’s “not a nobody.” He’s most interested in proving this to two people in his life — the woman he loves and his twin brother, Thomas, also played by Stanfield, who happens to be one of Jesus’ 12 apostles.

In a bid for the attention of Viridia, his lady love, Clarence enters a chariot drag race against Mary Magdalene (Teyana Taylor), borrowing his horse and vehicle from a local mob boss. When Clarence loses the race and the horse and chariot as well, he has to lay his hands on a lot of money, miraculously fast, to pay his debt and preserve his life.

“The Book of Clarence” film poster. (Image courtesy of Legendary Entertainment)

Clarence, an atheist, reckons he can save his hide, if not his soul, by joining his brother’s gang. But getting anyone to believe in his newfound belief is a rough go. John the Baptist (David Oyelowo) slaps the devil out of him but doesn’t buy Clarence’s interest in converting to the Jesus movement. When he applies to become the 13th apostle, the disciples laugh him out of the room. Barred from following the most popular messiah in town, he resolves to become one.

Clarence’s career as a false messiah presents some of the film’s most compelling material, about the reality of Roman occupation in first-century Palestine and to the earthly conceptions of salvation that their presence inspires in the occupied.

In this telling of the Jesus story, the Jews are a Black population living under white rule enforced by armed centurions patrolling the streets. At any moment, a soldier might stop a passing Judean and demand to see identification or search the Judean for contraband. When Clarence is detained in a roundup of local messiahs, the encounter echoes confrontations that provoked the uprisings of the Black Lives Matter era: The centurions mistake everyday objects for weapons while claiming to fear for their lives even as suspects are running away from them.

After Clarence’s trial, his mother, weeping on the side of the road, cries out, “They always take our babies!”

Samuel isn’t the first to draw parallels between Black life in America and the lives of colonized Jews in the first century. These scenes echo a central claim of Black liberation theology: God is Black.

When James Cone, Black liberation theology’s most famous proponent, dared to publish those words in 1969, he was pointing out that in Jesus of Nazareth God chose to be incarnated as a victim of imperial power rather than someone who wielded imperial power. While “The Book of Clarence” is a comedy, Samuels threads into his movie this essential insight, introducing Black liberation theology to audiences that may never have heard of Cone’s work.

The idea that Jesus was one of a small crowd of self-proclaimed messiahs at the time has shown up in biblical spoofs before, most memorably perhaps in Monty Python’s “Life of Brian.” The fact that the salvation they promised was political liberation from Roman rule is lost on many Americans. The ancient world assumed divinity was behind political reality.

Pontius Pilate (James McAvoy), left, and Clarence (LaKeith Stanfield) in “The Book of Clarence.” (Photo © 2023 Legendary Entertainment/Moris Puccio)

The modern church’s refusal to make this connection between the spiritual and political has driven many Christians away (including me). But more importantly, it ignores what the ancient Jews meant when they spoke of salvation: salvation from slavery in Egypt, exile in Babylon or the so-called peace of Rome.

So while Clarence doesn’t raise the dead, he does perform an act no less profound: He secretly gives the money he has extorted from his gullible followers to free a group of slaves. In doing so, he sentences himself to death, since that money was meant to pay off his debt. Most Christians I’ve met love to sing about Jesus freeing the captive, but don’t believe he would choose to free the enslaved. Clarence does.

To be sure, “The Book of Clarence” is no theological treatise, and even well-read Christians may be flummoxed by Samuel’s incorporating unfamiliar stories from the Gnostic Gospels and elements of magical realism. However, it would be wrong to interpret Samuel’s creativity as blasphemy. Samuel is as creative with his source material as the New Testament writers were with the Hebrew Bible.

But in its way of getting to the core of what the messiah means, the movie deserves to stand next to “The Passion of the Christ,” and Samuel has made himself someone believers and nonbelievers will want to watch.